This article was co-authored by Dunsky Partner Alex Hill and Dunsky Senior Consultant Patricia Lightburn and first appeared in AESP’s Energy Intel Q2 2021 edition. Re-published with permission.

Utilities have been leaders in driving energy efficiency and demand-side measures for decades. Regulated energy savings targets and dedicated ratepayer funding have spurred the creation of a range of programs, policies and incentives to encourage homeowners and businesses to retrofit existing homes and buildings. Yet over the past several years the retrofit landscape has evolved, resulting in new programs and policies entering the market, led by actors outside the utility sector such as local, provincial and federal governments as well as the private sector. Among these new initiatives has been a suite of financing programs aimed at accelerating deep retrofits by addressing persistent barriers such as high upfront capital costs and long payback periods. As these new initiatives expand in size and scope, utilities are often left wondering how they will impact their current demand side management programs. Will spending on new programs compete with utilities for ratepayer funds? Will they integrate with utility offerings, or pull customers away from existing DSM programs? How will savings be attributed? Despite these potential challenges, with careful planning and program design, there is an opportunity for non-utility financing programs to complement, rather than compete with, traditional utility programs.

The growing case for deep energy retrofits

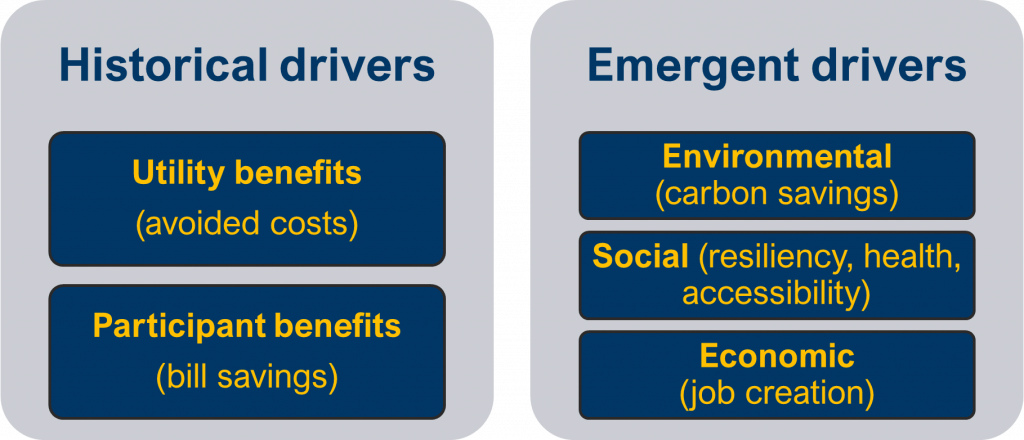

Over the past decade, new environmental, social and economic drivers have emerged to increase demand for deep energy retrofits. Historically, energy retrofits focussed on reducing the energy consumption of homes and buildings through energy efficiency and conservation, saving property owners money, and reducing the need for electric utilities to build out new costly electricity infrastructure. However, efforts by utilities to encourage ‘deep’ energy retrofits – with comprehensive upgrades to achieve significant depth of energy savings – have had limited success due to their longer payback period and limited cost effectiveness.

As efforts to tackle climate change grow, reducing emissions related to the energy consumption of buildings has become an increasingly important driver for deep retrofits. The IEA’s recent report Net Zero by 2050 estimates that to reach climate targets, 50% of existing buildings need to be retrofitted to net-zero ready by 2040[1]. The current focus on low-hanging fruit measures (i.e. lighting upgrades) falls short of meeting decarbonization targets. As a result, the retrofit industry needs to transition to deep comprehensive retrofits that avoid locking carbon intensive equipment, and can offset growing electricity demand from the electrification of buildings, transportation, and industry.

In addition to climate mitigation, with the impacts of climate change becoming increasingly prevalent and severe, there is an opportunity to leverage retrofits to improve the resiliency of buildings to climate-related disasters such as flooding and fires. Many aging buildings are also in need of seismic upgrades and improvements to support accessibility. Deep retrofits can significantly improve air quality and health outcomes, in addition to a range of other social co-benefits.

Finally, job creation has become a key driver for deep retrofits. The billions of dollars invested in energy efficiency and renewable energy projects through the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) was largely driven by the potential to create new jobs. Faced with the recovery from COVID-19, governments in both the US and Canada have committed significant spending to energy efficiency and climate initiatives in an effort to ‘build back better’. President Biden’s $2 trillion American Jobs Plan includes a commitment to retrofit more than two million homes and commercial buildings to create “affordable, accessible, energy efficient, and resilient housing” through block grant programs, the Department of Energy’s Weatherization Assistance Program, and by extending and expanding home and commercial efficiency tax credits. Canada has announced a range of new funding initiatives, including $2.6 billion over 7 years for grants, free energy audits, and recruitment and training of Energuide auditors, as well as $2 billion for large-scale building retrofits allocated to the Canada Infrastructure Bank.

Emerging Retrofit Financing Models

These new market drivers have led non-utility actors to establish a range of novel energy retrofit financing initiatives. For example, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) recently launched three new landmark financing programs representing an investment of nearly $1 billion focussed on accelerating retrofits in private homes, social housing and community buildings. Dunsky supported FCM with the design all three programs, finding new and innovative ways to tackle retrofit barriers and kickstart retrofit activity at the local level. In addition, the federal government recently announced that the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation will be providing homeowners with $40,000 zero interest loans to undertake deep retrofits.

In the U.S., ARRA helped to create new energy retrofit financing programs such as Efficiency Maine’s PACE Loan Program and Clean Energy Works Oregon. Thirty-five states established 51 revolving loan funds for energy retrofits and at least seven states and municipalities created loan loss reserves[2]. The America Jobs Plan includes a commitment to establish a new $27 billion financing tool called the Clean Energy and Sustainability Accelerator, which would mobilize private investment into retrofits of residential, commercial and municipal buildings, distributed generation and clean transportation.

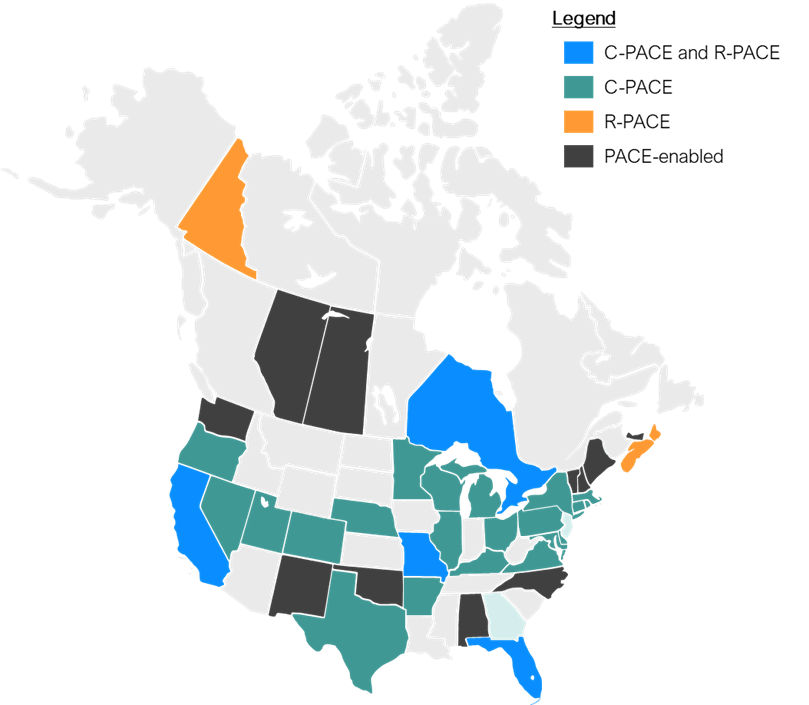

Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) programs have also emerged as a leading non-utility energy retrofit financing program. PACE programs leverage a range of public and private capital to provide low-cost long-term financing to residential and commercial building owners repaid via the property tax bill. In the US, PACE Nation reports that these programs have delivered 308,000 projects in 36 states plus D.C., representing $9.3 Billion invested and $18.7 Billion in economic impact.[3] PACE programs have also become popular in Canada, with enabling legislation currently in place or under development in seven Canadian provinces and territories. Dunsky has supported the design and evaluation of dozens of programs in Canada and the US and has seen first-hand that PACE programs can play an important role in accelerating retrofits when properly designed and implemented.

Figure 1: Map of current and planned PACE programs in North America (Source: Dunsky, 2021)

Green banks, infrastructure banks and other similar state and federal quasi-government institutions have also emerged as administrators of energy retrofit financing programs in recent years. Since the launch of the Connecticut Green Bank in 2011, over 21 similar green banks have been established in the US. In 2016, Dunsky supported the Connecticut Green Bank by developing and applying an evaluation framework to track its financing initiatives’ impacts and effectiveness, including a comparison of the GHG savings per dollar invested and the public cost per unit of clean energy delivered, both of which are key to the Bank’s core goals. In Canada, we recently supported the Canada Infrastructure Bank with the design of its $2 Billion Commercial Building Retrofit Initiative, focussed on achieving deep emissions reductions, driving market transformation, and supporting social and economic co-benefits. These banks and many others are stepping into the retrofit market to increase access to attractive financing for home and building owners, for example by offering below-market rates and longer terms that reflect the payback period of retrofit projects.

Opportunities for Utilities

The emergence of new financing programs raises the question of whether they present a threat or an opportunity for utility DSM programs across North America. There is a risk that new programs will compete or claim credit for savings achieved. For example, when financing is offered seamlessly at point of sale, it may be more attractive to property owners than incentives, which can have a cumbersome application process. Even if property owners apply for incentives in addition to financing, utilities may be concerned about the attribution of savings. In addition, non-utility financing programs may access ratepayer efficiency funds, thereby reducing the available budgets for utility DSM programs. Many of the green banks in the US are funded through a ratepayer surcharge, including the Connecticut Green Bank, the NY Green Bank, the Hawaiian Green Infrastructure Authority, the Rhode Island Infrastructure Bank, and Michigan Saves.

However, with deliberate planning and commitment by all players involved, utility programs can be effectively coordinated and integrated with non-utility financing programs to provide a more effective offering to home and building owners while avoiding duplication, optimizing the use of ratepayer and taxpayer funds, and supporting broader market coverage. Three approaches for utilities to consider include:

- Stacking programs to improve cost-effectiveness and market penetration: Utilities can continue to play an important role by helping to improve the cost-effectiveness of energy efficiency measures through rebates and incentives and providing tools and resources, such as building energy data, to customers to facilitate deep retrofits where the customer’s portion of retrofit costs are supported through financing programs. Securing attribution for energy savings when stacking programs is a valid concern for utilities. In our experience, non-utility financing program adminstrators are less concerned about attribution as they do not operate under utility DSM regulatory frameworks and cost-effectiveness rules. Furthermore, they are often focussed on reducing GHGs, leaving the door open for utilities to claim the energy savings, as is the case with the Canada Infrastructure Bank’s Commercial Building Retrofit Initiative. To ensure that energy savings attribution is not a barrier to the integration and stacking of programs for the benefit of customers (as well as the environment and the electricity system), utilities should identify and advocate for any required adjustments to their DSM regulatory frameworks.

- Delivering on-bill financing: Utilities can also deliver their own energy retrofit financing programs. On-bill financing or on-bill recovery programs provide low-cost loans to property owners to undertake energy retrofits, which are repaid via the electric utility bill. These programs have been implemented by 80 utilities in the US, and several across Canada, including by Manitoba Hydro which has been offering an on-bill financing program since 2001.[4] In some cases on-bill financing can be established as a repayment strategy attached to non-utility capital sources, thereby deepening the integration between utility DSM programs and non-utility financing.

- Supporting market transformation: Reaching climate targets will require a significant transformation of the retrofit market to attract private capital alongside, or in place of, public support. Utilities and non-utility actors can help scale up and transform the retrofit market by supporting standardization and consistency across the market. For example, applying mechanisms like the Investor Ready Energy Efficiency™ (IREE) certification within their application and underwriting processes can reduce transaction costs, and help standardise project development thereby help to establish retrofits as a distinct asset class.

There are several examples in the US of successful integration and collaboration between utility and non-utility models. The New York, Connecticut and Rhode Island green banks have all evolved their approaches over time to recognize the importance of integrating their offerings with existing utility programs.[5] For the Connecticut Green Bank, this resulted in a commitment to “examine opportunities to coordinate programs and activities…and to provide financing to increase the benefits of programs…so as to reduce the long-term cost, environmental impacts, and security risks of energy in the state.”[6] For the California Public Utilities Commission, Dunsky demonstrated how financing can work in conjunction with incentives to raise the combined cost-effectiveness of the two initiatives. In short, the addition of a loan loss reserve allowed homeowners to access low-cost capital to support their projects, which increased the net savings while offering significant interest rate reduction benefits.

Conclusion

The scale and pace of retrofits required to meet our climate target requires an all-hands-on-deck approach that leverages a range of programs, capital sources, and all levels of government, utilities and the private sector. Utilities have an historic opportunity to help solve the retrofit challenge and contribute to meeting our climate goals by working together with non-utility actors toward the goal of “leveraging up” existing utility programs with financing programs to achieve greater impact. Given the rapid growth of new energy retrofit models across North America, utilities face a significant risk of getting left behind if collaboration opportunities are not pursued.

The critical challenge that lies ahead will be to effectively integrate the different program offerings and align markets actors to offer a seamless pathway for property owners to pursue deep energy retrofits, complemented by government policy and regulatory mechanisms. Novel approaches may be required, including changes to the traditional utility model to enable utilities to play a larger role in supporting emerging environmental, social and economic objectives. The evolution of the utility model is well under way in many jurisdictions in North America. Given the imperative of taking action on climate, it’s time for these efforts to ramp up.

[1]International Energy Agency, Net Zero by 2050 (May 2021) https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050

[2] Goldman, Stuart, Hoffman, Fuller, & Billingsley (2011). Interactions between Energy Efficiency Programs funded under the Recovery Act and Utility Customer-Funded Energy Efficiency Programs. https://www.osti.gov/biblio/1008331

[3]PACE Nation, List of PACE Programs, (accessed May 10, 2021) https://www.pacenation.org/

[4]Environmental and Energy Study Institute, Interactive Map of Utilities with On-Bill Financing Programs (accessed May 10, 2021) https://www.eesi.org/obf/map

[5] Gilleo, Annie and Stickles, Brian (ACEEE) and Kramer, Chris (Energy Futures Group) (2016), Green Bank Accounting: Examining the Current Landscape and Tallying Progress on Energy Efficiency https://neo.ne.gov/info/pubs/pdf/ACEEE-Green_Bank_Accounting-DollarEnergy_Savings_Loans.pdf

[6]Connecticut General Statutes 16-245m (accessed May 10, 2021) https://www.cga.ct.gov/current/pub/chap_283.htm#sec_16-245m